By Mbabazi Pretta

Globally freedom of expression and media freedom are crucial to the functioning of democratic society. This reality has been particularly underscored since 2020, in the context of the coronavirus pandemic.

After Rwanda confirmed its first case of COVID-19, on 14th March 2020 strict measures have been imposed including the lockdown that has restrictions on a wide range of activities extending also to the media where limitations on freedom of movement have made it harder for journalists to move.

From then, at least 13 media practitioners have been either briefly detained or investigated and even prosecuted for not complying with the measures imposed to curb the COVID-19.

To date, three media practitioners are having court cases in relation to their conducts during the lockdown.

This February, Rwanda underwent Universal Periodic Reviews from Geneva based UN Human Rights commission and some of the countries were recommending to Rwanda to ensure that law enforcement agents cease and desist from the harassment and arbitrary arrest of journalists, and guarantee the rights of the press to continue working freely, including through the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and afterwards.

Every time Rwanda imposed lockdown, there was a list of essential services that were permitted to operate. Media services were not among.

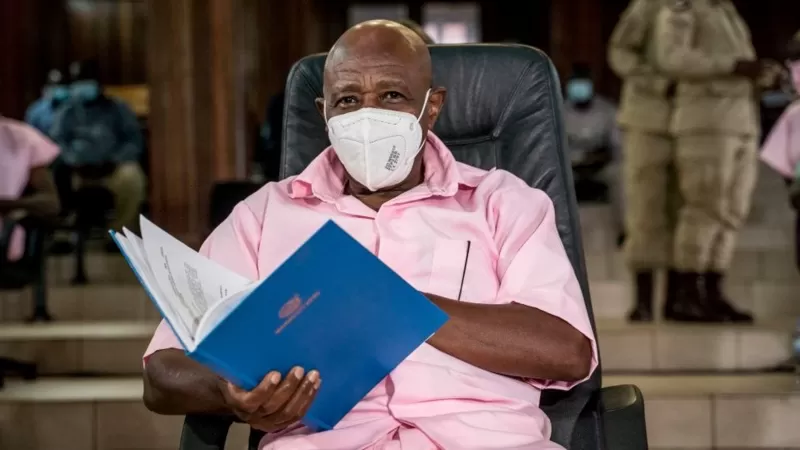

Interviewed on how this might be affecting their profession, one freelance journalist who once arrested, detained and investigated for not complying with lockdown measures while doing his work as journalists he emphasizes on the negative impact this is creating.

“There are always a list essential services published by the government, the media is not, it affects our work, I was once arrested and detained for a couple of days when I was covering curfew along with my colleague, we were provisionally released by the prosecution, he complained.

He further noted that “in a situation like this, the role of media should be to combat misinformation, to do so, we need to go on field to verify the information, but the measures in place and how we are treated have impacted on what the media can publish. Mostly we rely on internet and there is much misinformation”, he added.

There have been efforts to build capacities of journalists covering on Covid-19. For example in June last year, sixty-six (66) journalists from Rwanda were trained on promoting public access to fact-based information during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The training aimed at equipping journalists with requisite skills to effectively serve as frontline workers during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. However, to achieve this, relaxation on media practitioners’ movements as well as special actions are needed.

For the best of the profession there should be efforts to ensure that existing criminal and civil laws are not misused to clamp down on journalists during their work or others who speak up against crisis-related action measures, to adopt plan of actions for the safety of journalists, and to publicly and promptly condemn all acts of violence against journalists and carry out efficient investigations and prosecutions that bring those responsible to justice.

A report by Human Rights Watch on February 11th 2021, noted that at least 83 governments worldwide had used the Covid-19 pandemic to justify violating the exercise of free speech and peaceful assembly. Authorities have attacked, detained, prosecuted and in some cases killed critics, broken up peaceful protests, closed media outlets and enacted vague laws criminalising speech that they claim threatens public health.

“Governments should counter Covid-19 by encouraging people to mask up, not shut up,” said Gerry Simpson, associate crisis and conflict director at Human Rights Watch. Among countries where people have been detained for criticising government responses to Covid-19 include Bangladesh, China and Egypt, in at least 18 countries police has physically assaulted journalists, bloggers and protesters, in Uganda, security forces also killed dozens of protesters, according to HRW.